How can a teacher not only impart knowledge to students but also cultivate the mindset and skills necessary to learn independently? How can an engineer teach peers to integrate an immature technology into new applications while the best practices for its usage are being developed through their very work? The first question is central to pedagogy dating back at least to Plato’s Theaetetus and Phaedrus. The second is the analogue of the first in the engineering workplace; but is even harder because the shape of the technical problem is still being discovered and there is no set curriculum.

I was inspired by Mel Chua’s 7 Technique Cognitive Apprenticeship Theory to reflect on my past experience as a tutor and how similar technical communication flows have evolved in my current engineering practice. To adapt what Chua wrote, it is called “cognitive” apprenticeship because the teacher does more than teach the content: the teacher makes the metacognitive skills visible that are required to grow as a learner. This is central in the academic setting and made concrete by learning about a specific subject, unlike in a vocational apprenticeship where learning the craft is the primary goal and becoming a better learner is the side effect.

In new tech propagation, the tangible goal is to show how a novel technology can be used to build products, while the meta-goals include: communicating about and managing uncertainty, formalization of technique, connecting new work to existing bodies of knowledge and drawing from them where possible, and developing a “community of practice”. These might require changing training, test, release, and planning processes, how risk is assessed and communicated, or how user studies are conducted. Similar to how metacognition requires reflection on one’s learning processes to change oneself, the summary meta-goal of new tech propagation is to understand how the organization must change to effectively use it.

We’ll start with the flow of communication in Cognitive Apprenticeship (CA), and then show its parallels in New Tech Propagation (NTP).

Cognitive Apprenticeship

Original Document, adapted above

Most tutoring interactions start with students asking for help on something fairly specific, which is directing attention to one part of the problem space in bounding. Then I would usually ask what they know so far. This establishes the baseline of knowledge before the interaction, against which we will compare the new knowledge state at the end. This also functions as a reflection on what they’ve done already. Finally, their articulation of their knowledge or process of working through a problem removes the ‘expert blind spot’ of the instructor’s underestimation of the difficulty of a problem for a new learner.

I wanted to stay out of the direct didactic space for as long as possible, so I would then attempt to guide with questions. I tried to highlight the gaps in their understanding by asking them to consider missed cases, recall relevant principles, or push to where a governing model breaks down. This is scaffolding. Alternation of articulation and scaffolding is the ideal, because it models the process of students asking questions about their own understanding to resolve issues independently. If there is just one very specific issue with the student’s understanding, or I could cannot come up with guiding questions, I might go from articulation to coaching without scaffolding.

If guiding with questions does not get to the answer, I would then switch to guiding with direct suggestions in coaching. Here students work through problems with instructor direction. Failing this, I would demonstrate the process directly with worked examples and explain as I go: the modeling step. From modeling, I could then either ask the student to explain their own process as they work through a different problem (articulating) or to go back to the problem set or reference material (scaffolding) based on lingering issues of understanding.

The narration process was the one technique that I had difficulty integrating into my usual interactions. It is a different means of guiding with questions. Students are rarely familiar with attempting to explain as someone else works through a problem, and I’ve found is often a source of frustration because there isn’t a clear direction to the interaction. Most often it leads to coaching as is the usual step after scaffolding. In the past, I hypothesized that the reflection necessary to translate between the expert practice and their own practice is best done independently later, and would take too much time for narration to work within the context of a tutoring interaction.

Finally, the student reflects by comparing the state of their content and process knowledge before and after their interaction. I had shown how to ask questions and work through problems, and they might implicitly compare this with what they had done. I might also explicitly ask for “lessons learned” to encourage this reflection.

New Tech Propagation

Presenting a novel technology to others with the aim of integrating it into new applications requires many similar interaction patterns. However, unlike CA in an academic setting, NTP builds upon a network of communication with a presenter-peer relationship in place of teacher-student. Instead of a single tutoring session, these interactions unfold over weeks or months of attempted tech integration.

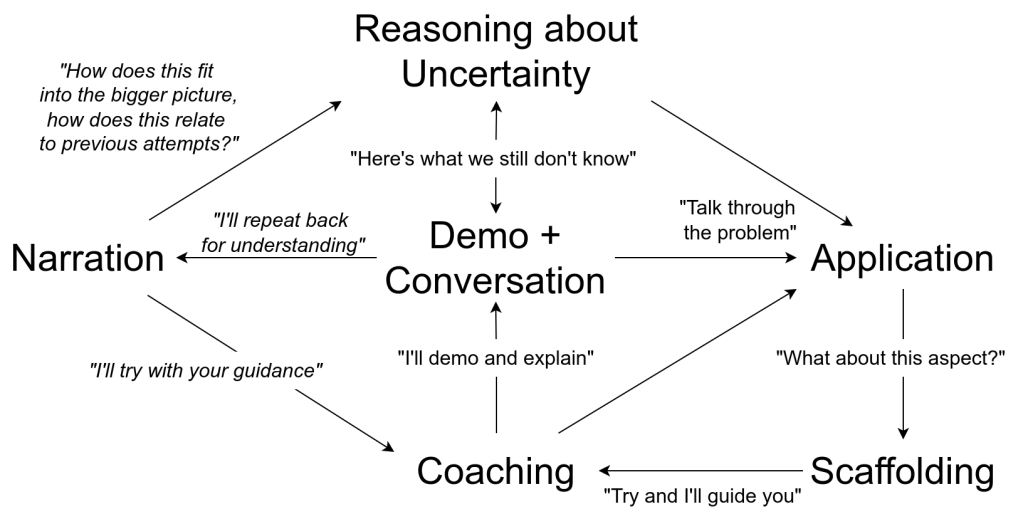

The core interaction is demonstration of the new technology and conversation with peers about its capabilities by the presenter which includes the “Modeling” and “Bounding” modes above. The most natural progression is to have peers attempt to use it by direct practice in “Application” which takes the place of “Articulation”. Hints are provided with Scaffolding which then leads to Coaching – attempted usage with direct supervision, which may return to Demo + Conservation. These interactions are all fairly similar to CA.

Narration takes on a new meaning because the peer may have knowledge that the presenter does not. The narrating peer attempts to describe his understanding of what the presenter is doing, which may include issues that the presenter does not see, connections to other fields, or past attempts to solve the same problem.

For example, suppose a computer vision team were evaluating “event cameras” for “camera traps” to capture images of Antarctic wildlife. Here “Alice” is the presenter and “Bob” is the reviewer who begins by narrating the proposal.

Alice: Event cameras differ from traditional cameras in that they only output changes in observed light for individual pixels instead of light received during an exposure window for all pixels, which makes them potentially well-suited to capture low-frequency events with large amounts of movement in the scene. They have the benefit of lower power consumption, which would conserve battery life of field-deployed camera traps, which means we can operate them for longer and justify the cost of more remote deployments.

Bob: I’ll repeat back to make sure I understand. You are proposing to move to a different system of image capture and animal detection that only responds to changes in pixel intensities with the intention of preserving battery life. In your view, by aligning the pattern of processing data with most valuable data, we have a more purpose-driven system. The claim is that power consumption would decrease because instead of processing all frames, we would process only the most interesting data. Is that correct? If so, how do we know that our power consumption would actually change?

Alice: Yes, that purpose-alignment and battery life are the proposed benefits. We can simulate this behavior in the lab in an end-to-end test by setting up a monitor in the front of an event camera and the baseline conventional camera system. Then, we can replay data we have received from the field that has a low frequency of animal movement events and monitor power consumption over time.

Bob: That sounds reasonable to validate the power consumption claims. Do we know that we have explored other possible optimizations to improve battery life? Would the event camera give the same quality of data as the conventional camera? How do we know that we will capture all of the same events?

Alice: Separately from the battery life test, we can compare the behavior of the event camera and the conventional camera through a simulation of each as image processing algorithms on our existing data set to get the precision and recall of detected events.

Bob: Is our existing data set biased because it has been captured with conventional cameras? How well will we be able to simulate the effect of using these event cameras instead? What does a pixel reading from an event camera really mean in comparison with a conventional camera?

Alice: Because our existing cameras capture at 30 FPS, and the responsiveness of event cameras is much faster, we cannot make perfect comparisons between the two platforms using our existing data. Event cameras can respond within microseconds. But the sum of all pixel change events that would happen between two frames is probably approximated by the inter-frame diff. We can validate this with a new data set of a side-by-side comparison of the two camera types in a single field study.

Here, Alice presents the idea, Bob starts by repeating it back to ensure understanding and tries to find the limits of what is currently known about event camera technology. Bob is pushing to learn how the two camera types will be compared. Alice recognizes Bob’s focus and responds with design of experiment proposals. To further the ‘tech propagation’ Bob could then create the detailed experimental design (Application), which Alice would review. Bob’s design would give Alice the opportunity to Scaffold or Coach about anything Bob missed about event cameras.

Either party could have chosen to move to discussion about the cost of the two types, more specifics about the gains in battery life, the number of different providers of these types, how durable they are in the field, the relative difficulty of developing image processing algorithms for event cameras, etc. It is not critical to touch on every aspect during the “Reasoning about Uncertainty” and it may be better to move to Application on the most important topics first.

Internally, Bob may be thinking about the right way to store the new streams of data from event cameras, if they will be queryable in the same way, or if the change in source data will allow the animal experts who receive the images to distinguish between different polar bears. Alice may be thinking about the long-term sustainability of this camera system because it is less commonly employed. By cycling between the different “Cognitive Apprenticeship” techniques, Alice and Bob can accelerate the communication of these unstated ideas. Each element of the cycle advances the technical evaluation and also prompts reflection on how their organization would have to change to support it.